Hur detta skall se ut beror på var du återanvänder informationen. Det kan exempelvis se ut så här:

Ronny Gunnarsson. "Introduktion till kvalitativa metoder" [på INFOVOICE.SE]. Tillgänglig på: https://infovoice.nu/introduktion-till-kvalitativa-metoder/. Informationen hämtad July 17, 2025.

| Suggested pre-reading | What this web page adds |

|---|---|

| This web-page gives you a birds perspective of empiric-holistic (qualitative) approaches to research. You will find lots of links from this web-page to other web-pages providing more information. |

OBS! http://infovoice.se/fou/bok/10000002.shtml

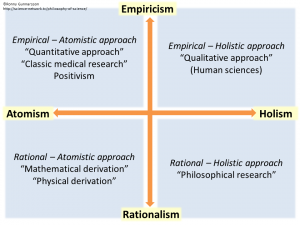

Qualitative methods does not use figures and numbers. Hence, they don’t use any kind of statistics. Qualitative methods are based on observations (empiricism) and use a holistic approach. Hence, it is better to use the term empiric-holistic paradigm (=empiric-holistic approach) rather than the ambiguous “qualitative methods” (see figure to the right). This is elaborated upon further down.

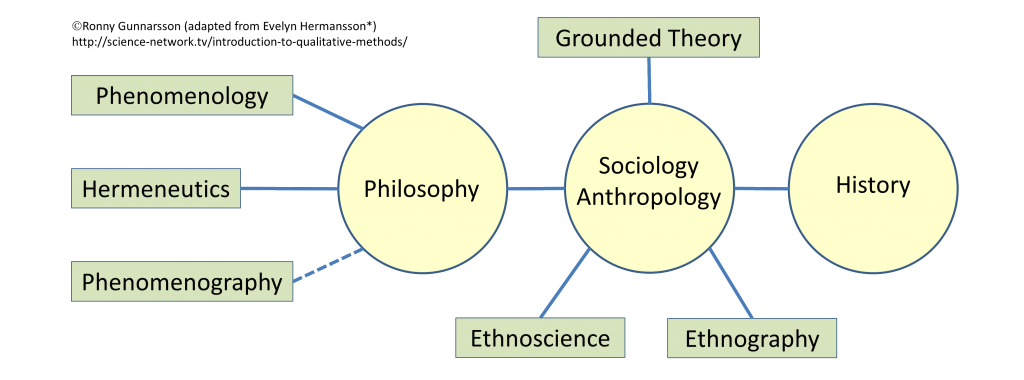

Research methods used within the empiric-holistic paradigm (“qualitative methods”) is more or less rooted in the philosophy of science. Hence, awareness of philosophy of science is considered more important when using qualitative methods compared to using statistics. Phenomenology and hermeneutics are example of methods with a strong link to philosophy of science. It might be worth mentioning that phenomenology and hermeneutics can refer both to an empiric-holistic method and to a specific philosophical orientation.

Common concepts

Let us start by explaining some words commonly used:

- Epistemology is a major branch of philosophy, which, among other things, is about how we go when we develop new knowledge. Epistemology states there are four major types of paradigms.

- Paradigm (=theoretical frame = perspective). The world map of philosophy of science (figure above) shows four major different paradigms. Paradigms are the spectacles through which we see the world. Each paradigm embraces different methods that share the basic principles of this paradigm. The empiric-holistic paradigm, containing qualitative methods, is one of these four major different paradigms in philosophy of science.

- Method (Analytical method). Multiple different methods are used within each paradigm. Within the empiric-atomistic paradigm we have lots of different statistical methods. This page provides an overview of the different methods we have within the empiric-holistic paradigm.

- Data collection techniques (= data collection methods). To avoid confusion between “methods” I prefer to talk about “data collection techniques” rather than “data collection methods”.

Qualitative methods is an ambiguous concept

(Detta avsnitt är under konstruktion. Vi beklagar olägenheten.)

Theories underpinning empiric-holistic approaches

Research methods within the empiric-holistic (“qualitative”) paradigm has its roots more or less in philosophy, sociology and anthropology (se figure below). Phenomenology and hermeneutics are example of approached having a very strong link to philosophy of science and more specifically to the life world perspective first described by Edmund Husserl.

(* The figure above is adapted from Evelyn Hermansson at Gothenburg University, Sweden)

Some analytical methods have a strong link to underpinning theories while others have a less pronounced link and furthermore some, like content analysis, has almost no link. Hence, content analysis is often referred to as a method without underpinning theory.

Differences and similarities between methods

Most analytical methods within the empirical-holistic paradigm have more in common than what separates them. Most methods in this paradigm are characterized by:

- The researcher should be aware of his preconceptions (= pre-understanding = preconceived opinions = prejudices) and how this may affect data collection and analysis.

- Open data collection.

- Collected data is encoded / transformed into units of meaning.

- Units of meaning are arranged and combined to form one or more categories.

- Often, several categories are combined into one (or more) overall themes / essences / theories / main interpretations. Examples of this highest abstraction level are:

— phenomenology – Essence

— Hermeneutics – Main interpretation

— Grounded theory – Theory

— Content Analysis – Main category

Analytical methods within the empiric-holistic paradigm differs in respect of:

- What kind of knowledge is most interesting? Is it the life-world perspective (as in phenomenology and hermeneutics) or human behavior with possible interactions with other people (as in grounded theory)?

- Should you begin to analyze data during data collection (as in grounded theory) or should all data be collected before analysis begins (as is usually done in phenomenology)?

- Do you think that the researcher, by being aware of their own pre-understanding, can be objective (as in phenomenology) or do you believe that the researcher interprets whether it is the intention or not. You may accept (and even embrace) interpretation if you think it is impossible to avoid this and instead let interpretation drive the process of coding data (as you do in hermeneutics).

Some methods in the empirical-holistic (qualitative) paradigm have a clear and well-described approach when analyzing collected data. Examples of such approach is grounded theory. Other methods are not as well defined, such as content analysis. Within the research methodology phenomenology there are different variants of how to analyze. If you say that you have used a phenomenological method, you should also specify in detail how you have done. Sometimes reference is made to previously described analysis models (for example, phenomenological approach according to Giorgi’s methodology).

Choosing the best approach – the chicken or the egg?

The best approach when choosing which method within the empirical-holistic (qualitative) paradigm that suits best is to first first look at the aim of the study. You can do that by looking at the questions posed within brackets in the overview below. Based on this choose which method best your research question. This is the ideal order of events in the research process.

It is quite common that researchers have a certain worldview and as a consequence are used to think within a specific paradigm. This may make them prone to stick to aims and research questions that is best answered by methods they are familiar with. A person who is well-placed in, for example, phenomenology is likely to get caught up in new issues that make it possible to choose phenomenology again. Thus, the interaction between aim/research question and selection of appropriate method is not always straightforward. Quite common a researcher choose aim and research question suitable for a specific method rather than the other way around. This is not necessarily bad but it might be good to be aware of the rationale for picking a specific method.

Qualitative study design

Qualitative methods can be placed within the empirical-holistic paradigm (see figure above). The exception is analysis of concepts that falls within the rationalistic-holistic paradigm (see figure above). These approaches (study designs) has traditionally been grouped as:

| Approach | Focus |

|---|---|

| Case study | Provide an in depth description of a case and what we can learn from that case. A case can be one person, family, group, community, company, country, etc. |

| Ethnography | Aim to describe the characteristics of a culture (or subculture) and what we can learn from them. |

| Grounded Theory | Aim to develop a new theory around social phenomenons (interactions between people) based on (grounded in) actual observations. What happens and how do people manage? |

| Historical | To describe past events to understand the present and anticipate what might happen in the future |

| Narrative | Analyse the stories people tell and offer possible interpretations. |

| Phenomenology | Describe lived experiences and condensate this to an essence of how this lived experience can be described. |

| Biographical Study | An in depth description and analysis of the life experience of one person. |

| Action Research Studies | Implement changes (actions) and describes what happens without aiming for generalizable truths. Hence, not using randomisation or calculating statistics. |

| Content analysis | Focus on finding (as in inductive content analysis) or verifying (as in deductive content analysis) a pattern among any data consisting of verbal or visual observations. |

| Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) | TDF aim to identify barriers and enablers to change of behaviour. It is mainly used in implementation research. |

Below is an alternative grouping of qualitative methods (inspired by Anne Nyström, nurse and doctor of philosophy at Gothenburg University, Sweden):

- Methods focusing on language and communication between humans.

- Content or process analysis (“What does the choice of words and the organization of the conversation tell us about this group of people?”)*

- Ethnoscience (“What can be inferred about people’s world-view from their choice and use of words?”)

- Methods focusing on repeating events / themes / patterns in human life. These methods are looking for patterns describing the lives people live. They focus on human actions or the forms, patterns and structures forming daily life.

- Grounded theory (“What is the pattern describing what is happening…?”)

- Phenomenography (“What are the different ways to perceive…?”)

- Ethnography (“How do people in this culture perceive and manage…?”)

- Content analysis (What is the pattern emerging around…?)*

- Critical research / Feminist Research (“What are the social phenomenons linked to…?)

- (Action research)**

- Methods searching for meaning in people’s experiences or written texts. These methods have a life-world perspective trying to describe how people experience and interpret the world around them. They aim to acquire a deeper description, interpretation and understanding of people’s experiences.

- Hermeneutics (Allows interpretation to be incorporated into emerging patterns of meaning. Acknowledge and allows, even encourage, some degree of interpretation / subjectivity from the researcher.)

- Phenomenology (Recommends not allowing or limiting interpretation to be incorporated into emerging patterns of meaning. Tries to be “objective”.)

- Content analysis (What is the pattern emerging around…?)*

- Life stories

* Content analysis is unfortunately used for two quite different methods. One is a simpler form of method within the empiric-holistic paradigm. The label content analysis is sometimes also used when occurrence of different phenomenon is counted and described with descriptive statistics. This latter form of content analysis resides in the empiric-atomistic paradigm rather than the empiric-holistic paradigm.

** Action research has components of counting numbers and hence is not purely a method within the empiric-holistic paradigm.

Concept analysis focusing on the question “What is the significance / meaning of the concept…?” …is often used in qualitative research. However, concept analysis is not directly an empiric-holistic approach. It lies within the rationalistic-holistic approach (philosophical research).